Summary

Since the military coup in Myanmar in February 2021, the ruling junta has suppressed the human rights of the population, intensified abuses in the country’s decades-long armed conflicts, and exacerbated the economic and humanitarian crises. Many people have fled the oppression, fighting and inadequate aid to go to neighboring countries, joining the millions of Myanmar migrants, refugees and asylum seekers already living abroad. Over 4 million are now in Thailand, nearly half of whom are undocumented, facing the constant threat of harassment, arrest, and deportation.

This report examines the situation for Myanmar nationals in Thailand since the coup. Many are refugees under international law, even though they have not been recognized as such and there are limited ways in which they can regularize their status in Thailand. These undocumented Myanmar nationals are compelled to seek out security and a livelihood and avoid being returned to repression, conflict and humanitarian crises in Myanmar.

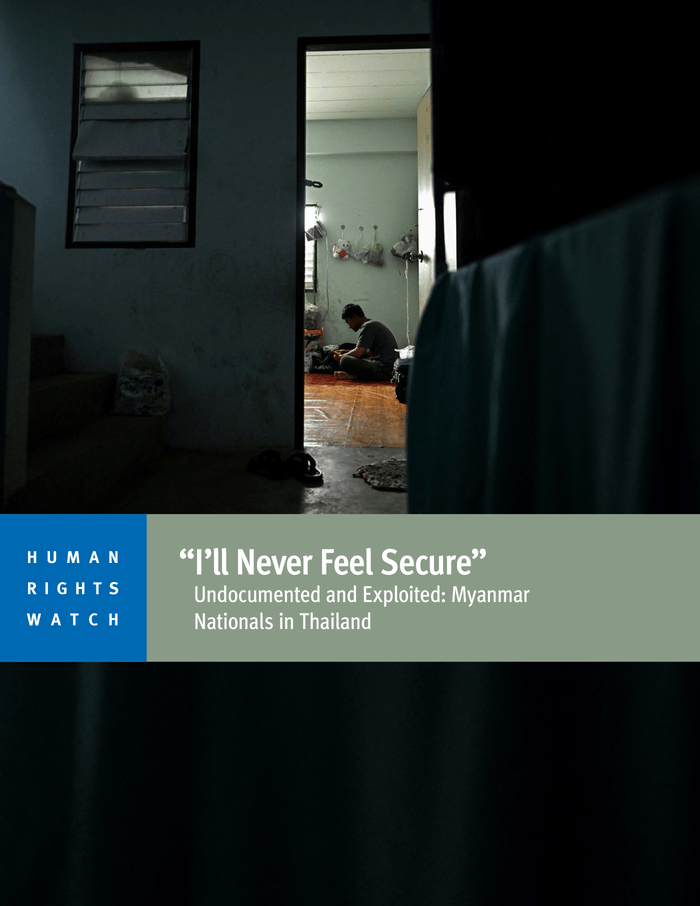

Thailand does not recognize refugees, and the limited measures it has in place for “protected persons” are effectively closed to most Myanmar nationals. As a result, many Myanmar nationals, including children, have no legal access to basic health care, education or work. The reality for many is self-imposed house arrest to avoid the constant risk of extortion, not only from random encounters with Thai police, but also from the semi-formal systems Thai security personnel use to extract money from undocumented migrants.

On February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military staged a coup and arrested the country’s elected civilian leaders, including de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint. Mass protests quickly proliferated in cities and towns nationwide. The military junta, called the State Administration Council, and led by Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, soon turned on the anti-coup demonstrators, carrying out mass arrests and using deadly force. The security forces targeted individuals perceived as threats to the junta: activists, students, journalists, humanitarian workers, lawyers, and religious leaders. Those taken into custody were subjected to torture, rape, enforced disappearance, and prolonged imprisonment without a fair trial.

The armed groups in ethnic minority areas that have been fighting successive Myanmar governments since independence in 1948 were joined by members of the civil disobedience movement fleeing urban areas. In the ensuing years, hundreds of anti-junta People’s Defense Forces have formed, notably in areas previously tied to the military, often cooperating with the ethnic armed groups. The military has responded with intensified operations, including widespread aerial and artillery attacks against towns and villages, harming civilians and damaging civilian infrastructure. An abusive conscription law was put into effect in 2024,

The junta has severely hindered the delivery of humanitarian aid to communities most at risk. Humanitarian needs have reached alarming levels, with an estimated 19.9 million people – more than a third of the population – in need of assistance, including more than 3.5 million internally displaced. A devastating 7.7-magnitude earthquake on March 28, 2025, near Mandalay resulted in more than 3,500 deaths and widespread destruction. The United Nations estimated that the number of people needing humanitarian services surged from 1 million to 5.2 million in the affected areas.

All of these factors have led to an upsurge in people fleeting Myanmar.

Thailand has long been a destination country for migrant workers across Southeast Asia. Most come from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, with the overwhelming majority coming from Myanmar.

Approximately 82,000 mostly ethnic Karen refugees from Myanmar have been living in closed refugee camps along the Thai-Myanmar border for decades. Freedom of movement is restricted, and the population survives on little to no income and humanitarian aid services, a situation that has worsened since the 2025 cuts to US funding.

Hundreds of thousand more Myanmar nationals have fled oppression and armed conflict to cross the long and porous border into Thailand. The Thai government has allowed new arrivals to stay in informal temporary stay areas near the border, but has at times pushed them back. None of the arrivals since the coup have been permitted to enter existing refugee camps and Thai officials place strict restrictions on their movement and access to humanitarian aid and basic services.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) conservatively estimates that over 4 million Myanmar migrants live in Thailand and that up to 1.7 million are undocumented. The IOM notes that in 2023 alone, 1.3 million Myanmar migrants crossed into Thailand. While many Myanmar nationals cross into the country seeking a livelihood, particularly since Myanmar’s economic collapse and its humanitarian crisis, many are fleeing persecution, conflict, and the junta’s recent enforcement of its conscription law. Migrant workers and refugees are not mutually exclusive categories, even though Thai policy seems to regard them as such.

Thailand is not a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Refugee Convention) or its 1967 Protocol. The country has no refugee law or formalized asylum procedures that are applicable to all nationalities. Instead, in 2023, the government introduced a new National Screening Mechanism (NSM) under which some individuals who are unable or unwilling to return to their countries of origin due to fears of persecution can seek protection. Those deemed eligible are granted legal recognition under Thai law as “Protected Persons.” While presented as a step towards greater international protection, the National Screening Mechanism and its implementing regulations largely exclude certain nationalities from access, including migrant workers from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. In addition, those who present themselves before the screening mechanism are still vulnerable to arrest and detention under Thailand’s immigration laws, which deem undocumented foreigners “illegal,” discouraging many from applying.

The focus of this report are the abuses Myanmar nationals face in Thailand. Exposed to arrest and detention and the constant risk of deportation, Myanmar nationals self-restrict their movements, living in hiding and out of sight. Human Rights Watch found that Thai police frequently stop and interrogate Myanmar nationals, extorting them with the threat of arrest and detention if they fail to pay bribes, considerable sums for those with little income. Human Rights Watch found this practice to be prevalent in the border town of Mae Sot in Tak province, where a lucrative business of threats and bribes has resulted in the authorities referring to Myanmar nationals as “walking ATMs.”

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that these practices left them scared and intimidated; having fled human rights abuses, armed conflict and a humanitarian crisis in Myanmar, they felt marginalized and exploited in Thailand.

Thai security personnel have engaged in racketeering through a semi-formalized system of extortion that involves “selling” unofficial “police cards” to Myanmar nationals looking for a pathway to documentation or even just seeking to avoid arrest. The only real option for those not willing or able to purchase such cards is self-imposed house arrest.

In Mae Sot, interviewees said that they paid a monthly “subscription fee” of approximately 300 Thai baht (THB) (US$9) and provide a photograph of themselves with a “broker” who gives them a telephone number. This telephone number is a direct line to the broker who can be contacted if the Thai police take the person into custody. The broker will then assure the police that the person is paying a monthly subscription and should be released.

This loose and unofficial form of “protection” may involve seemingly small sums of money, but for many interviewed it is a large amount. They cannot afford this monthly “service” and only do so when they can find work or need to travel. An 8½-months-pregnant woman living in a forested area near Mae Sot said that she struggled to pay the transportation costs to the clinic for her first pre-natal scan (an examination that should be performed in the first 24 weeks of pregnancy). She feared arrest because she is undocumented and could not afford a police card.

The families hiding in remote, rural areas outside Mae Sot with whom Human Rights Watch met were cut off from electricity and clean running water. Upwards of 20,000 Myanmar nationals are estimated to be living in these rural areas with limited access to basic services.

Even those paying a subscription fee are not fully protected against deportation. Mass deportations of Myanmar nationals, including children, continue across the country, without regard to the risk they might face. One woman said that despite paying for herself and her 12-year-old niece, the Thai immigration authorities arrested them both, held them in a detention facility for nine days, and then deported them to Myanmar.

Most of the Myanmar nationals who spoke to Human Rights Watch were in the process of applying for or renewing a migrant worker’s card, commonly known as the “pink card.” This is the main document available to Myanmar nationals in Thailand that provides a legal status. The process requires an employer to sponsor the migrant worker. Every interviewee, whether renewing their documentation through a regularization window (a specific period during which the Thai government allows undocumented or migrants to regularize their legal status) or applying for the first time, relied on a paid broker to handle the process, and paid often exorbitant fees to purchase the necessary documentation and manage the convoluted process. In all cases examined by Human Rights Watch, the listed employer on the pink card was not their actual employer, but a fabricated one.

While a migrant worker’s card provides some protection from arrest, detention, and deportation, it is not a legitimate, protective pathway for people who are likely de facto refugees. The use of brokers to provide fake employers exposes people to arrest should they face investigation by the Thai authorities. In addition, the inflated sums – up to WHAT?? — to purchase documentation are prohibitive for many, who may make only THB250 (US$7) per day as laborers — when they can find work. Being protected as a refugee under international law should not have to depend on making such payments.

Human Rights Watch urges the Thai government to enact legislation that establishes criteria and procedures for recognizing refugee status and providing asylum that meets international legal standards. Refugee status should be open to all nationalities according to the same criteria, consistent with the international refugee definition, including complementary forms of protection for people fleeing conflict.

In the interim, Thailand should introduce a temporary protection framework for Myanmar nationals (see the appendix), recognizing the immediate needs of thousands of people who have fled persecution or the country’s conflicts. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has repeatedly said that there should be no forced returns to Myanmar: “People fleeing Myanmar must be allowed access to territory to seek asylum and be protected against refoulement.”

Against this backdrop, Thailand should implement a system to allow Myanmar nationals the opportunity to apply for legal residency in the country, permitting them the right to work, and giving them access to healthcare and education services. Thailand’s parliamentary Committee on National Security, Border Affairs, National Strategy and National Reform, as well as many civil society organizations, have made similar proposals to ease the exploitation and suffering of hundreds of thousands of undocumented Myanmar nationals.